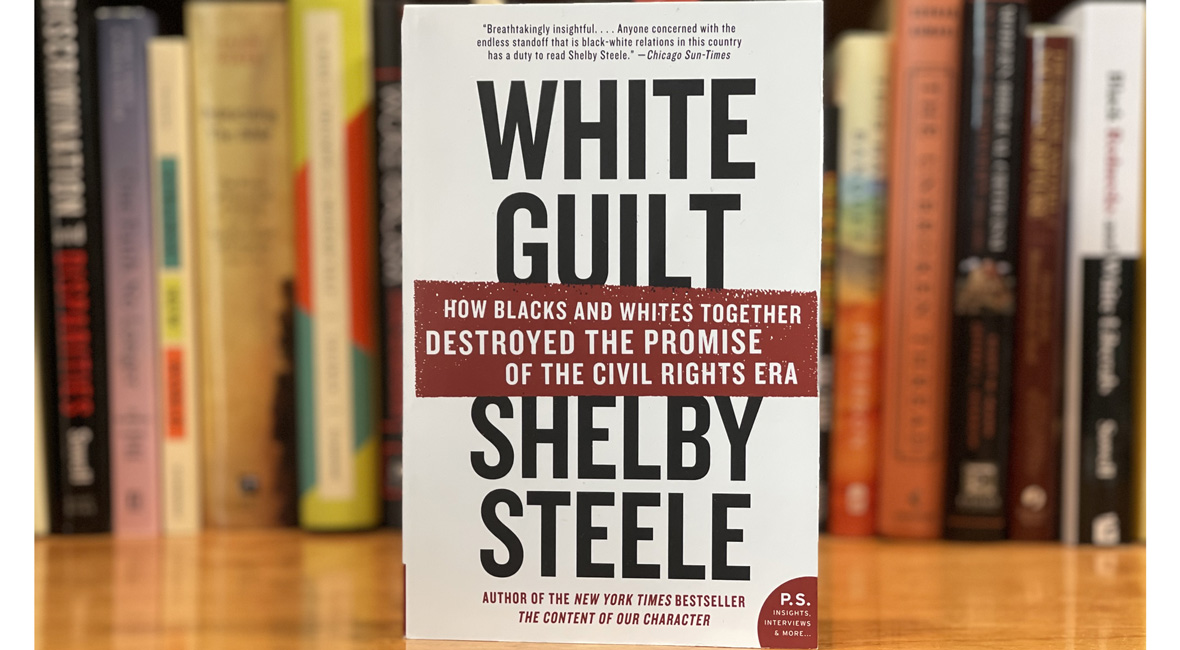

Summary of White Guilt

In White Guilt, Shelby Steele ties together two journeys: one, his drive up the California coastline on a beautiful autumn day, and two, his socio-political evolution from radical leftist to “conservative black man.” Long drives often give us time to reflect on important matters, and one can’t help but feel transported along the winding roads beside the sea with Steele as he uses the occasion of Bill Clinton’s impeachment to ponder how much America has changed in his lifetime. He grew up in the age of blatant, public racism, lived through the Civil Rights Movement, and then came of age in the years after Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed. The difference between his childhood and his young adult years is stark, being characterized by white calls “white guilt,” which he defines as “the vacuum of moral authority that comes from simply knowing that one’s race is associated with racism.” (24)

Moral authority, particularly its absence among and the search for it by whites, is one of three important themes in White Guilt. The racism found throughout America’s history, once finally acknowledged by whites, has emptied white America (and American institutions) of moral authority, not just in matters of race, but in everything. The quest to regain moral authority by whites must now run through matters of race. “Whites (and American institutions) must acknowledge historical racism to show themselves redeemed of it, but once they acknowledge it, they lose moral authority over everything having to do with race, equality, social justice, poverty, and so on.” (24) Moral authority is contingent upon proving that you aren’t racist. The inheritance of historical guilt by whites means that they are obligated to blacks because only blacks can give whites their moral authority back. Much of the virtue signaling that we see among the Woke, therefore, is at least in part the effort of Woke whites to regain the moral authority forfeited by their racist ancestors.