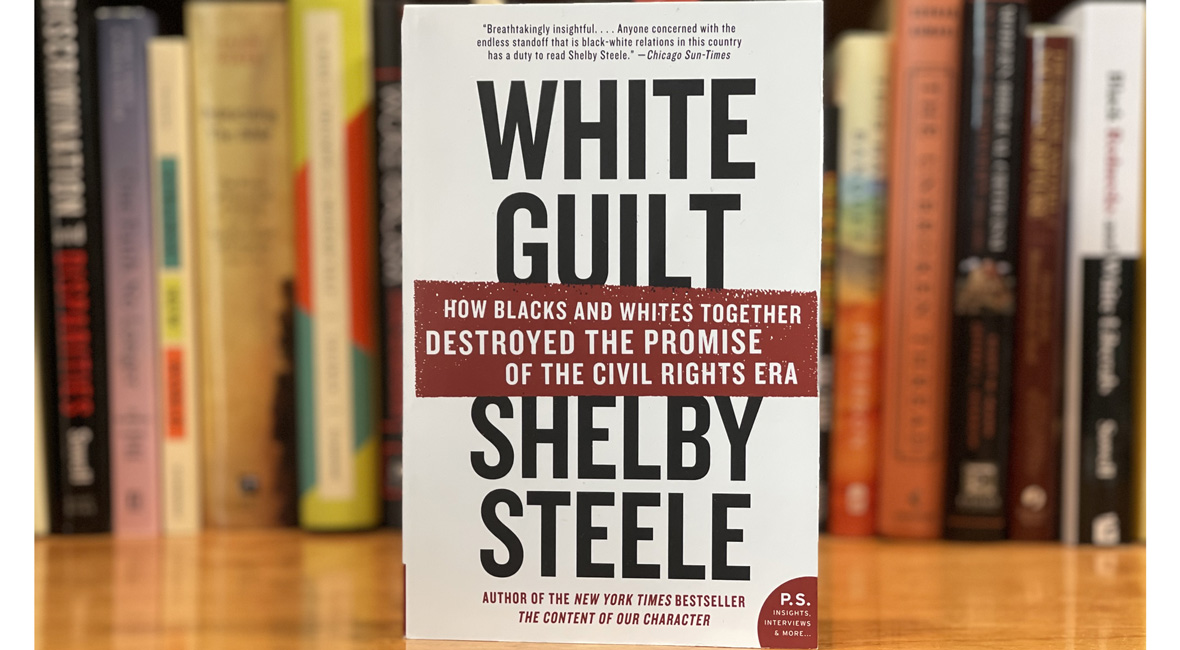

White Guilt by Shelby Steele

Summary of White Guilt

In White Guilt, Shelby Steele ties together two journeys: one, his drive up the California coastline on a beautiful autumn day, and two, his socio-political evolution from radical leftist to “conservative black man.” Long drives often give us time to reflect on important matters, and one can’t help but feel transported along the winding roads beside the sea with Steele as he uses the occasion of Bill Clinton’s impeachment to ponder how much America has changed in his lifetime. He grew up in the age of blatant, public racism, lived through the Civil Rights Movement, and then came of age in the years after Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed. The difference between his childhood and his young adult years is stark, being characterized by white calls “white guilt,” which he defines as “the vacuum of moral authority that comes from simply knowing that one’s race is associated with racism.” (24)

Moral authority, particularly its absence among and the search for it by whites, is one of three important themes in White Guilt. The racism found throughout America’s history, once finally acknowledged by whites, has emptied white America (and American institutions) of moral authority, not just in matters of race, but in everything. The quest to regain moral authority by whites must now run through matters of race. “Whites (and American institutions) must acknowledge historical racism to show themselves redeemed of it, but once they acknowledge it, they lose moral authority over everything having to do with race, equality, social justice, poverty, and so on.” (24) Moral authority is contingent upon proving that you aren’t racist. The inheritance of historical guilt by whites means that they are obligated to blacks because only blacks can give whites their moral authority back. Much of the virtue signaling that we see among the Woke, therefore, is at least in part the effort of Woke whites to regain the moral authority forfeited by their racist ancestors.

The second important theme of White Guilt is responsibility. Who is responsible for the uplift of blacks in America? Steele makes the case that, after King’s death, responsibility came to be viewed as a tool of oppression. To say that blacks must be responsible for their own lives and choices became an act of victim-shaming. Therefore, responsibility for black advancement and uplift was, in the years following the Civil Rights Movement, redistributed from blacks to whites. The prevailing progressive view became that only whites could uplift blacks. As Steele poignantly states, the result was that “black militancy became…a militant belief in white power and a…militant denial of black power.” (60) Progressives took black advancement out of black hands and put it into the hands of whites. He laments, “No worse fate could befall a group emerging from oppression than to find itself gripped by a militancy that sees justice in making others responsible for its own advancement.” (62) The centering of whites in the struggle for black uplift came to be known as “social justice.” White guilt creates the illusion that social justice is an agent, not a condition. In other words, white guilt believes that blacks can only advance if more whites take up the cause of their advancement. In a damning statement Steele writes, “white liberals and American institutions…keep seducing blacks with social justice as though it were also developmental.” (63)

The third theme of White Guilt I want to highlight is dissociation, which Steele understands as the dis-association of whites from American history, ideals, and institutions. White guilt drives whites to disconnect themselves from their country and history. By doing so, modern whites demonstrate their superiority over whites of the past. At least I’m not like those racists back then, they reassure themselves. “Dissociation is virtue,” Steele writes. (155) It legitimizes all other virtues and excuses all vices. You can be an adulterer but you cannot be a racist. Dissociation makes you good because, under the burden of white guilt, social morality holds greater cache than individual morality. Who and what you reject is more important than who and what you accept. Steele is quick to point out, however, that dissociation is a shortcut to moral authority. “In choosing dissociation over principles the Left became impotent.” (176) Those who dissociate from the past are alienated from the principles required to solve today’s moral and social problems.

My Personal Takeaway and Recommendation

The more I read White Guilt, the more I became befuddled at how racial progressivism continues its ascendancy in our culture. Has no one read Shelby Steele? Are they just ignoring him? How does racial progressivism survive the quote I highlighted above? White Guilt is an absolute wrecking ball to, well, white guilt. As the subtitle of the book states, we really have destroyed the promise of the Civil Rights era, and I’m not sure that we’re ever going to get it back. Sadly, I don’t have much hope for the Church in America, either, as it seems so many of our leaders have been sucked into regressive Woke racialism that Steele exposes as mere white supremacy. Books like this are vital because they show us how we have lost our way, something that we absolutely cannot do in matters of race.

I highly encourage everyone to read and reflect on White Guilt. It is not a difficult read — less than 200 pages overall — and Steele’s prose is engaging and insightful. The chapters are short and punchy, filled with helpful wisdom even beyond the subject of race in America. I’ll leave you with one final quote from the second to last page that I think sums everything up quite nicely: “If you want to be free, you have to make yourself that way and pay whatever price the world exacts.” (180)

“social morality holds greater cache than individual morality. Who and what you reject is more important than who and what you accept. Steele is quick to point out, however, that dissociation is a shortcut to moral authority.” — This motivation to latch onto and broadcast “what you reject” has become so important. This almost defines the woke-ism of today in my opinion.

Wokeness honestly sounds so much like late 20th century fundamentalist Christianity, except in reverse.