With the landmark decision from the Supreme Court this week, striking down DOMA, proponents of gay marriage have scored a huge, if not final, victory in their pursuit of marriage equality. The Court’s decision reflects popular opinion. In our society, marriage (and all of its benefits) is understood as a civil right, and therefore cannot be legally denied to anyone who wishes to be married. While I disagree with this understanding of marriage, and personally believe that homosexual practice is on the spectrum of sexual immorality, I am not overly concerned by what this ruling means for our society. What concerns me, rather, is what I’m hearing and seeing in the Church, and how it understands what the Bible has to say about homosexual practice.

There is a movement happening within the Church, and particularly within Evangelicalism, to reconcile the Church with the homosexual community. I believe in this movement. I want to be a part of this movement. I am convinced that this is one of the things that God is doing in the American church today. However, I’m concerned that, in an effort to follow God’s leading, we are throwing the baby out with the bathwater. As Christians are pursuing reconciliation and love, the Scriptures are being misinterpreted, misunderstood, ignored, or even denigrated. In a well-intentioned attempt to be humble and contrite about sins committed against homosexuals (and those sins are real and many), many Christians are abandoning the millenia-old biblical sexual ethic, and, more importantly, the understanding of the authority of Scripture over the life of the believer.

I want to be clear about something. The problem lies not with what the Bible says or does not say about homosexuality; the problem lies with the hostile attitudes, condemning words, and proud hearts that Christians have had toward homosexuals. What I see and hear happening, though, is that for many Christians the Bible is the problem. When the Bible becomes the problem, and as a result you throw it under the bus, you step outside of historic, orthodox Christian faith. So what I’d like to do in this post is address some of the issues regarding Scripture and homosexuality that I’ve seen raised in the past few years.

1. Jesus never talked about homosexuality.

This is, perhaps, the most common objection to the biblical teaching on homosexuality. This is also a true statement. Jesus never directly addressed homosexuality; or to put it more accurately, the Gospel writers did not include statements about homosexuality in their books. If Jesus did say something about homosexuality or homosexual practice, it has been lost to history. The inference that many people make from this silence is that Jesus, therefore, approved of homosexual practice, or at the very least he approved of loving, monogamous, homosexual relationships.

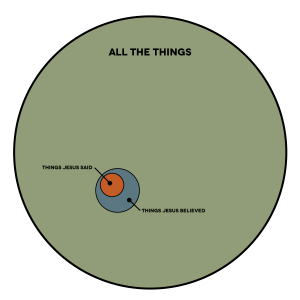

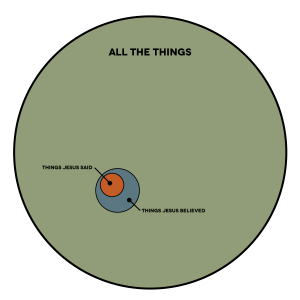

The trouble with this reasoning is that arguing from silence is the weakest argument one can make. Take a look at the picture on the left. You have three circles. The largest circle is “All the things,” which symbolizes everything somebody might possibly believe. The smallest circle is “The things Jesus said,” and the circle that is slightly larger than that is “The things Jesus believed.” I believe that it’s safe to assume that Jesus believed more things than what the Gospel writers credited him as saying. In other words, Jesus believed more than he said. That, I take it, is self-evident.

The trouble with this reasoning is that arguing from silence is the weakest argument one can make. Take a look at the picture on the left. You have three circles. The largest circle is “All the things,” which symbolizes everything somebody might possibly believe. The smallest circle is “The things Jesus said,” and the circle that is slightly larger than that is “The things Jesus believed.” I believe that it’s safe to assume that Jesus believed more things than what the Gospel writers credited him as saying. In other words, Jesus believed more than he said. That, I take it, is self-evident.

However, the trouble comes when trying to determine what, exactly, lies outside of the red circle but inside of the blue circle. Some assume that, because of the importance of homosexuality, Jesus would have spoken against it if, in fact, he believed that homosexual practice was wrong. But because he did not speak of it, he must have either, a) not been too concerned about it, or b) approved of it. (A third inference would be that, because Jesus didn’t talk about it, neither should the Church.)

While I agree that homosexuality is a really important issue, there are a lot of other issues of equal importance that Jesus also did not talk about. Just in relation to human sexuality and sexual activity, Jesus did not address any of the following issues:

Polygamy/polyamory

Bisexuality

Cross-dressing

Rape

Child sexual abuse

Bestiality

Group sex

Public nudity or exposure

Using the same logic as above, we must assume that Jesus either, a) wasn’t too concerned about these issues, or b) approved of them. Of course, this is absurd. If we believe that the following statement is true, Jesus didn’t talk about homosexuality, therefore he approved of the exercise of it, then by mere reasoning we can substitute any activity for homosexuality, as long as Jesus did not expressly condemn it in the Gospels. Besides the list of sexual activity above, we could include extortion, kidnapping, and a host of other evils. There are even some good things that Jesus never spoke about; for example, romantic love. Arguing from silence breaks down into absurdity because it is based on mere speculation. It is unreasonable to believe that, because Jesus never explicitly talked about or condemned homosexuality, he therefore approved of the practice of it.

In fact, when Jesus speaks about sexual ethics, he makes it clear that his position on human sexuality is even stricter than what is found in the Old Testament. For Jesus, sexual holiness and wholeness extend to the individual’s heart, so that external adherence to biblical laws is not a sufficient sexual ethic in the kingdom of Jesus. Whether Jesus was talking about lust or divorce, he consistently added to the teaching of the Old Testament, indicating that he expected more from his disciples than what the Bible called for. It would be shocking, then, if Jesus were lax on the issue of homosexual behavior, which is condemned in Leviticus 20.

2. The prohibition of homosexuality in the OT is right next to the command not to make a garment of two types of material.

The implication of this statement is that, because nobody pays attention to the garment command, neither must we pay attention to the sexuality command. This same reasoning pops up with certain commands in the New Testament, particularly about women speaking in church or having short hair.

I am somewhat sympathetic to this objection. Why, after all, must Christians be hard-lined on sexual behavior and not other behaviors? When did we decide which Scriptures we could ignore and which we had to enforce? If we’re going to let men have long hair and women have short hair in our churches, then we should have a good explanation of how we’re obeying the spirit and intent of those commands rather than just ignoring them altogether.

With that said, it is hard to ignore that there is a consistent sexual ethic to be found in Scripture. While Leviticus 20 presents the bare bones outline of this ethic, it is expounded upon in many other places in the Bible, and even made stricter by Jesus. Unlike the kosher food laws, the Old Testament’s sexual ethic is never abolished in the New Testament.

Furthermore, the selective application of Scripture by some Christians is not a reasonable argument for the selective application of Scripture by other Christians. And just because some Scriptures seem absurd and outdated to us doesn’t mean that other Scriptures, whether in adjacent chapters or in the other Testament, should be treated as such.

3. David and Jonathan were gay lovers.

The question of the nature of David and Jonathan’s relationship has gotten a lot of attention lately. Indeed, their relationship was complicated and intense. Jonathan took off his robe in front of David. David said that his love for Jonathan was greater than the love of women. They kissed and wept together. So they were gay, right? Not necessarily.

First of all, Jonathan almost immediately recognized that, though he was Saul’s firstborn son and rightful heir to the throne of Israel, it was David who would become king. Rather than become his rival, however, Jonathan became David’s friend. The act of taking off his robe (and also his tunic and sword) and giving it to David is most likely the symbol of Jonathan’s surrender of the throne to David. The covenant that they made together, recorded in 1 Samuel 18, is not a covenant of marriage, but a covenant of power and of the throne of Israel.

Secondly, the love that David and Jonathan had for one another was not necessarily sexual in nature. The Hebrew word found in this passage (ahobah) has a wide spectrum of meaning, much like our own English word “love.” According to Holliday’s Lexicon, the word can mean the love between a husband and wife, the love between friends or people in general, or God’s love for his people. The overwhelming majority of occurrences in the OT describe the love between friends or the love between God and his people. It’s important to note, too, that most marriages in the Ancient Near East were not based on romantic love, particularly for someone with the political power of David or Jonathan, so the love that David had for his wives was likely not as strong a force in his heart as the love I have for my wife. (I readily admit, of course, that this is speculative. But it’s important that we remember just how different our culture is from Israel in David’s time.)

Third, the kiss was a common greeting and “goodbye” in ancient Israel. Examples of two men kissing can be found in Genesis 29:13, Genesis 33:4, 1 Samuel 10:1, and 2 Samuel 19:38-39. None of these kisses are sexual in nature. For a much fuller treatment of the relationship between David and Jonathan, please check out this post from pleaseconvinceme.com.

4. The NT authors were talking exclusively about abusive homosexual relationships and cultic sexual practice.

The implication of this statement is that, in places like Romans 1:26-27, 1 Timothy 1:9-11, and 1 Corinthians 6:9, Paul is talking about the abusive homosexual relationships, common in Roman culture, between an older, dominant man and a younger, passive man, and not monogamous, same-sex relationships based on love and respect. He may also have been talking about sexual activity in the worship of idols, which is a common theme in idolatry both in the Old and New Testaments.

This argument might be convincing if Paul were Greek or Roman. Though he was a Roman citizen, Paul was a Jew, through and through. He was, at one point, a Pharisee–a teacher within the strictest sect of Judaism. As I have already mentioned, there was a strong sexual ethic within Judaism, and particularly within Pharisaic Judaism, that would have understood homosexual practice, as well as many other sexual activities, as contrary to God’s command. The defining element of the nature of the relationship was not whether it was abusive or cultic, but that it was homosexual. While Paul would have also condemned heterosexual cultic sexual practice (and any other kind of cultic sexual practice), as well as abusive heterosexual relationships, because of his strict upbringing in Torah, he would not have accepted or embraced monogamous same-sex relationships.

But what about when he recognized Jesus as Messiah and his life was changed by God’s grace? As we have already seen, God’s grace does not necessarily mean a relaxing of the sexual ethic of the Old Testament. In fact, based on what Jesus communicated in the Sermon on the Mount and elsewhere, the sexual ethic of Jesus’s kingdom is more strict than what is found in Torah. We have every reason to believe, especially given what Paul says in 1 Corinthians 6:18-20, that Paul, following the lead of Jesus, draws a clear line demarcating appropriate sexual behavior for the believer, and homosexual practice lies on the far side of the line.

5. The authors of Scripture knew nothing about sexual orientation.

This is probably true, but I don’t think it matters. The Bible never tells us to “be true to ourselves” or to “follow our hearts.” The truth is, when we follow Jesus, we are called to say “No” to the natural desires of our hearts. None of us are oriented to take up our cross and follow Jesus. None of us are oriented to lay down our lives for our friends, love our enemies, or go the second mile for anybody. There’s nothing natural about following Jesus. And yet these are the basics of being a Christian.

For all we know, the authors of Scripture knew nothing about being introverted and extroverted. There is so much that Jesus demands of me that forces me to set aside fundamental aspects of my personality (INTJ–the best!) for the sake of others, himself, and his kingdom. I find, very often, that being a Christian, much less a Christian leader, is very unnatural and difficult for me.

I want to finish by saying this: Jesus is opposed to anything that is more fundamental to your identity than himself. Jesus is opposed to anything that leads you away from closer communion with himself. Jesus is opposed to anything that you love more than himself. Sexual orientation is not more fundamental, more important, or more true than the person of Jesus Christ.

The book is arranged in an easy-to-read format, with each section divided up into subsections (or subchapters) that typically run just 3 or 4 pages. A guy could easily read a subchapter between meetings, in a waiting room, or before work each day. The accessibility of the format, as well as the content, makes this book a prime candidate for small group studies. While the material of the book doesn’t go as deep as, say, John Eldridge’s classic Wild at Heart or LeAnn Payne’s Crisis in Masculinity, it may be more likely to reach men on the fringes of our churches–those who come because their wives demand it, and who are too distracted by the allures of this world to invest any of their time or energy into a relationship with Jesus.

The book is arranged in an easy-to-read format, with each section divided up into subsections (or subchapters) that typically run just 3 or 4 pages. A guy could easily read a subchapter between meetings, in a waiting room, or before work each day. The accessibility of the format, as well as the content, makes this book a prime candidate for small group studies. While the material of the book doesn’t go as deep as, say, John Eldridge’s classic Wild at Heart or LeAnn Payne’s Crisis in Masculinity, it may be more likely to reach men on the fringes of our churches–those who come because their wives demand it, and who are too distracted by the allures of this world to invest any of their time or energy into a relationship with Jesus.