Antony Flew was a leading philosopher and atheist of the mid to late twentieth century. He taught at several distinguished schools, including Oxford, Aberdeen, and Reading. He also taught at Bowling Green State Universtiy, near my hometown of Toledo, Ohio. He passed away in April of this year.

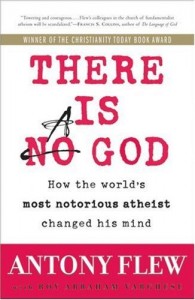

In There is a God, Flew lays out his journey from atheism to deism, briefly sketching each of the arguments that influenced the evolution of his thought. Because I am not a philosopher, I will not attempt to summarize those arguments here. The book itself is short enough (less than 220 pages) and colloquial enough to not be overwhelming. Many of us may need a Philosophical Dictionary nearby to understand some of the terms, but most folks can easily follow the arc of the story.

The book is a narrative rather than a philosophical treatise, and it tells the story of Flew’s life as it pertains to the issue of the question of God. He tells tales of his many interactions with Christian and Theist philosophers in debates and dialogues. While there was no singular moment of illumination, it was the cumulative effect of these interactions which brought him to his “conversion.” (I put conversion in quotes because he did not become a Christian, so far as I know. He simply came to believe in a “divine Mind”.)

The book is a narrative rather than a philosophical treatise, and it tells the story of Flew’s life as it pertains to the issue of the question of God. He tells tales of his many interactions with Christian and Theist philosophers in debates and dialogues. While there was no singular moment of illumination, it was the cumulative effect of these interactions which brought him to his “conversion.” (I put conversion in quotes because he did not become a Christian, so far as I know. He simply came to believe in a “divine Mind”.)

The “conversion” sent a shockwave through the philosophical and atheistic communities. Flew was a pillar of atheism, one of the greatest minds and most ardent defenders of the “faith”. His admission of the existence of a divine Mind was too much for some to bear. There were accusations that the co-author, Roy Abraham Varghese, manipulated Flew, by then an old man, into publishing this book. While Flew admitted that Varghese did the actual writing, he asserted that the thoughts were his. In the years leading up to his death, Flew publicly declared, again and again, that he had become a deist (and denied becoming a Christian or a Theist).

The guiding principle of Flew’s life, and the through line of this book, is the Aristotelian line, “follow the argument wherever it leads.” It was his commitment to this ideal that ultimately led him out of atheism and into belief in a divine Mind. The primary evidence, as laid out in his book, is the complexity of DNA and the lack of a naturalistic explanation for the evolution of reproductive capability. These issues led him to belief in a divine Mind, which of course is not all the way to the Christian Creator God, but is a large leap of faith for an atheist of his stature.

The book includes two appendices, one by Varghese and the other by N.T. Wright. While Flew was “converted” to the concept of a divine Mind, he did not believe in divine revelation, though he was open to being convinced. Of all the religions claiming divine revelation, he thought Christianity to be the only one worth noting.

“I think that the Christian religion is the one religion that most clearly deserves to be honored and respected whether or not its claim to be a divine revelation is true. There is nothing like the combination of a charismatic figure like Jesus and a first-class intellectual like St. Paul. …If you’re wanting Omnipotence to set up a religion, this is the one to beat.” (185-6)

Wright’s contribution is a brief but potent sketch of his defense for the existence of Jesus, his divinity, and the historicity of the resurrection. This alone is worth the price of the book, and if you’ve never read Wright (what are you waiting for?!), will give you a solid introduction to his three large volumes on Jesus.

I don’t know where Antony Flew stood on the issues Wright raised when he died in April. There’s something oddly refreshing, for me at least, that his book was about his conversion to deism and not to evangelical Christianity. It seems more honest that way, I guess. But of course I hope that he came to acknowledge Jesus as the Son of God, and to receive the forgiveness offered him from the cross.

Questions: How does the “conversion” of a notorious atheist strengthen your faith? What are the most important philosophical questions regarding the existence of God? What are the most important pieces of scientific evidence in this debate?